Social housing that puts design first is creating communities and homes residents are proud of

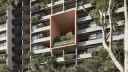

There are plans for a commercial pool at the Midtown MacPark community housing redevelopment.

(Frasers Property Australia)

With a pool, gym, community gardens, and open-plan living, Tanya Rahme initially thought her social housing apartment was part of a scam.

"When I received a call last October from my housing provider telling me about this utopia, I thought, 'those bloody scammers'," she said.

Ms Rahme spent nearly four years couch surfing, living in women's shelters, and sleeping in her storage unit while going days without showering.

She never imagined being homeless at 50 years old, but she struggled to get back on her feet after falling victim to "dodgy mortgage lenders".

Then the news came about Midtown MacPark, a community apartment project in Sydney's Macquarie Park.

"I have friends who live in social housing and hearing some of their stories filled me with terror," Ms Rahme told the ABC.

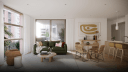

"But I was shown this wonderful space with really beautiful interiors that you can not only live in, but really enjoy living in and make your own.

"I thought I'd won the lottery. And I still feel like that."

Social housing neglect

Governments have been criticised for neglecting social housing development.

A report by the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council in May found social housing had declined as a share of the housing stock for three decades, down from 5.6 per cent in 1991 to 3.8 per cent in 2021.

Currently, about 175,000 households nationally are on the social housing waiting list.

Australia also has some of the least affordable housing among advanced economies, according to the report.

Prioritising design

Among its recommendations, the council noted the importance of creating good-quality, "secure and dignified" housing.

Living in poor-quality housing can have impacts on mental health, "increases the likelihood of developing chronic health conditions, and [it] increases the risk of domestic and family violence," the report states.

Midtown MacPark is among a handful of new projects taking an approach to social housing that focuses on design for community cohesion and quality of life.

Rachelle Elphick from Mission Australia, which partnered with Frasers Property Australia and Homes NSW on Midtown, described it as "changing the direction of social and affordable housing".

"The whole community is thoughtfully designed," she told the ABC.

"We've had so many emotional moments where people have cried walking through the doors."

Ms Rahme has been living in her apartment for nearly a year, and has been furnishing her space with goods she finds at council clean-ups.

She said she was proud to have a place where her adult children could "pop into mum's for dinner".

"I also love the sense of community," she added.

"There's a real energy of people wanting to get involved."

Building community

Midtown was formally Ivanhoe Estate, which was made up of 259 public housing dwellings.

It has undergone a major redevelopment to include a mix of private and social housing.

Among the 3,300 apartments planned, 950 will be community and 130 will be affordable homes.

Community housing is managed and often owned by not-for-profit organisations.

Affordable homes include social and other housing initiatives.

They are either bought or rented usually at no more than 30 per cent of gross household income.

Currently about half a million Australian households are living in, or have requested to live in, a form of social housing, according to the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI).

And the demand is expected to reach more than 1.1 million by 2037.

Buildings from the Midtown Macpark housing redevelopment.

Liam Davies, a lecturer in sustainability and urban planning at RMIT university, cautioned that there was evidence social mixing did not always work.

There have been instances of public housing renewal projects bringing in private tenancies and creating levels of tension.

"The people buying those new apartments are not the same income or demographic level as the people living in the public housing," he said.

"What you do is you end up isolating them on the site."

But he said this might not be the case with Midtown because the apartments were more affordable.

Mission Australia has been working to create "a cohesive and inclusive community" by providing on-site support services and organising gatherings.

Ms Rahme said this had also been happening naturally, with people spending time in the gardens and getting together for dinners.

"No-one really cares what building you live in," she said.

"People have come to this with eyes wide open, really wanting it to be the best sort of living space it can be."

'Something else was possible'

Since 2015, Nightingale has been experimenting with community housing models.

The not-for-profit organisation builds design-led affordable housing, with about 20 per cent of its buildings assigned to community housing providers for those most in need.

Rents are calculated based on a percentage of the tenant's income.

Nightingale CEO Dan McKenna said a group of disgruntled architects set out "to show that something else was possible".

"There is the old model of, 'Let's build one big tower with 100 per cent social housing tenants,'" Mr McKenna said.

"We're big advocates of dispersing people throughout all buildings."

The group has so far built nearly 700 apartments in 20 Nightingale buildings across the country.

From single parenting to a 'village'

Tiffany moved into Nightingale's Skye House building in Melbourne with her 10-year-old son in 2022.

The 55-year-old single mother was homeless for three years, moving across three states in the hope of finding affordable, available housing.

After staying with friends and spending time in emergency accommodation, Tiffany, who preferred to only provide her first name, never thought she would end up living in a brand-new apartment.

"I was in shock. It took me ages to realise it was actually mine," she told the ABC.

Tiffany said she and her son were thriving among the "village" of six Nightingale buildings in Brunswick, a lively inner-city suburb.

"I'm just so happy here … I've met friends in the building and through other buildings within the community."

The highest-priority groups chosen for the 20 per cent of affordable apartments include Indigenous Australians, people with disability, and single women over 55.

The other 80 per cent are privately owned and go to market using a ballot process.

Mr McKenna said they were trying to bring "fairness" back to the housing market.

"It's not the typical kind of sell-to-the-highest-bidder model, which a lot of housing actually is," he said.

"We literally put people's names in a hat."

Midtown and Nightingale were both designed with community in mind.

A main feature of Tiffany's apartment block is the communal rooftop where there are gardens, a group laundry, space to host events, and even a bathhouse.

"It's pretty amazing," Tiffany said.

"My 10-year-old is such a social butterfly. He knows more people than me.

"They host little gatherings on the rooftop, and he'll often go up there and join in by himself."

No one-size-fits-all solution

Dr Davies said while it was positive new projects were coming to fruition, there was a need for more housing that was designed to suit a range of households.

Intentional design approaches are often contributing to a shift towards smaller one and two-person dwellings.

And he said people on social housing waiting lists were already facing strict allocation limits.

He also warned about approaches to public housing redevelopments where previous tenants were "uprooted".

Ivanhoe Estate was closed in late 2018 for demolition and redevelopment.

About 35 former residents were returning to live at Midtown.

"I don't think there's actually a problem with redeveloping public housing estates. The problem is currently it requires all the tenants to be moved off site for many years, until the new site is developed," he said.

He suggested staging redevelopment so pockets of the site were rebuilt over time, and involving tenants through collaborative design that met their needs.

View original article here.